Piano Lessons

Virtuosity & Piano Artistry

In the sphere of piano performance or piano artistry there are few human activities where the necessity for extraordinary physical prowess is so closely aligned with the greatest intellectual and emotional capacities.

The virtuoso must possess a memory capable of maintaining thousands of pages of music in the mind and fingers, under the stress and distractions of public performance; the virtuoso must be cultured and self-aware, musically able to convey the great range of meaning embodied within a chosen repertoire; the virtuoso must project both physical excitement and emotional communication; and the virtuoso must experience life to the fullest while remaining cloistered with an instrument in a relentless quest to maintain his or her craft at its highest level.

http://www.theartofpianoperformance.com/

Study Piano Performance in Boca Raton & West Palm Beach

Are Pianists the Super-Athletes of the World?

Learning Strategies for Musical Success

Physiologist Homer Smith cites skilled piano playing as one of the pinnacles of human achievement because of the “demanding muscle coordination of the fingers, which require a precise execution of fast and complex physical movements”. This remarkable human ability provides an insight into the power of the brain. Consider Frédéric Chopin’s popular but challenging Fantaisie-Impromptu. This work requires playing approximately nineteen notes per second. The performer must learn these notes to such an extent that conscious attention to them is virtually no longer necessary. This is the aim of any playing of music—to render the technical demand to an almost unconscious level. Daniel Levitin says, “Plain old memorization is what musicians do when they learn the muscle movements in order to play a particular piece”. Much of this repetitive practice routine is more or less an algorithmic task. There’s nothing particularly creative about learning the motor mechanics of a phrase…

View original post 308 more words

Toccata BWV 915 by Johann Sebastian Bach

Toccata BWV 915

The toccata an extensive piece intended primarily as a display of manual dexterity written for keyboard instruments reached its apex with Johann Sebastian Bach in the eighteenth century. Johann Sebastian Bach’s seven Toccatas incorporate rapid runs and arpeggios alternating with chordal passages, slow adagios and at least one or sometimes two fugues. The Toccatas have an improvisational feel to them analogous to the fantasia. Unlike the Well Tempered Clavier, English suites, French suites and other sets, Bach himself did not arrange them into a collection. When JS Bach left Weimar the Toccata at that time was out of fashion. They became in vogue again after his death and were organized into a collection. The g minor Toccata is one of the more obscure of the toccatas and has rarely been performed partially due to the extensive second fugue with its many thorny passages of the contrasting gigue rhythm. However, this Toccata has many fascinating effects. It is one of the only pieces by JS Bach that has dynamic markings of piano and forte.

The g minor Toccata opens with a flourish, which leads into an expressive adagio with an improvisational feel. The adagio is interrupted by a lively allegro in the relative major key of Bb which includes concerto-ritornello passages of imitation and solo/tutti passages. A deceptive cadence leads back into the adagio where it was interrupted and then closes the adagio with a perfect authentic cadence in Bb major. This aspect provides a unity to the different movements of the Toccata. The other striking example of unity between movements is the beginning flourish repeated at the end of the second fugue, which leads into a formal closing of the work.

The extended fugue in a gigue has a subject of an ascending sequence combined with a countersubject of driving triplets. The subject of the fugue has twelve expository entries followed by eleven entries. There are inversions, permutations, combinations of minor with major, which is varied by modulating to the subdominant, then to Eb major and then back to the g minor tonic. The vivacious counter subject of driving triplets provides a symmetrical balance.

To learn more about Fugues please read my other Hub: The Art of Fugue

http://jamilasahar.hubpages.com/hub/The-Art-of-Fugue

For More Information on Piano Lessons in Boca Raton or Via Skype:

‘St Francois de Paule marchant sur le Flots’ Franz Liszt

‘Among the numerous miracles of St. Francis of Paola, the legend celebrates that which he performed in crossing the Straits of Messina. The boatmen refused to burden their barque with such an insignificant looking person, but he paying no attention to this, walked across the sea with a firm tread’…Franz Liszt

The story is beautifully captured in Liszt’s music. The calm strength of the opening hymn-like music is throughout the piece pitted against the roaring and crashing of the waves (represented by rushing scales and tremolos), finally emerging victorious in a glorious fortissimo restatement at the end of the piece.

Granados Inspiration for ‘The Goyescas’

Quejas, ó la Maja y el Ruiseñor—The Maiden and the Nightingale

Granados often called the poet of the piano is frequently compared with Chopin due to the highly ornamental figuration as well the influence of nationalist folk music in their melodies and rhythms. Granados indicated they are Goya-like or Goya-esque hence the name ‘The Goyescas’.

Regarding Goyescas, Granados wrote, “I am enamored with the psychology of Goya, with his palette, with him, with his muse the Duchess of Alba, with his quarrels with his models, his loves and flatteries. That whitish pink of the cheeks, contrasting with the blend of black velvet; those subterranean creatures, hands of mother-of-pearl and jasmine resting on jet trinkets, have possessed me.”

The story of Goyescas is based on a series of six paintings from Francisco Goya’s early career, inspired by the stereotypical young men and women of the majismo movement. “majos” and “majas” are known for their bohemian attitude and spirited nature. In this tale of the goyescas, the four main characters are Rosaria an enchanting aristocratic woman, her lover Fernando the captain of the royal guard, Pepa the maja and Paquiro the majo / toreador. A love triangle is formed when Paquiro flirts with Rosaria and invites her to a dance. Although she ignored his advances, Fernando did observe Paquiro’s advances and now does not trust Rosaria. Pepa also infuriated by Paquiro’s attentions to another woman seeks revenge. Later at the party, tensions are high and culminate in the two majos seeking to fight a dual. Later Rosaria sings a mournful ballad to a nightingale as she fears she will lose him. Fernando approaches and she begs him not to go to the dual and tries to reassure him of her devotion only to him. He still does not fully trust her, and wishes to prove his majismo, and promises to return to Rosaria victorious. Alas, Fernando is fatally wounded in the dual, and the grief stricken Rosaria drags him back to the bench where she sang to the nightingale and professed her love to him. Fernando then dies in her arms.

Quejas o La Maja y el Ruisenor the fourth piece of the Goyescas is the only one in the set with a key signature. The monothematic piece is based on a folksong Granados heard sung by a girl in the Valencia countryside. Granados transforms the haunting melody into five variations. It is the scene where Rosaria sings mournfully to the nightingale. The variations start in f# minor, move to b minor and back to f# minor which follows with the nightingale responding in a beautiful cadenza of elaborate figuration. Although there are five variations of the folksong, the piece is written in an improvisational manner where the variations flow directly into the next.

Quejas, o la Maja y el Ruiseñor

Alicia de Larrocha’s mesmerizing performance of Granados beloved

Quejas, o la Maja y el Ruiseñor (aka The Maiden and the Nightingale)

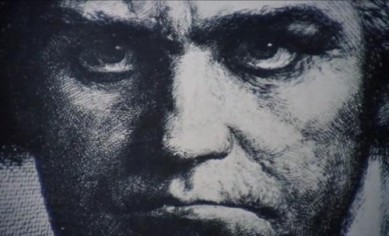

Beethoven’s Tempest

The Tempest

In 1800-1802 Ludwig van Beethoven experienced devastating internal turmoil in trying to come to terms with his hearing loss. To the outside world, his life seemed to be ideal, with his success as a virtuoso pianist and as a successful, sought after composer in Vienna. He gradually began to withdraw from society and friends, however, as he felt it would be detrimental to his successful career as a musician if people found out he was going deaf. People felt he was being misanthropic, yet it was quite the opposite. Beethoven lived in a great deal of solitude and loneliness due to his impending and eventual complete deafness, which would eventually have a profound effect on his spiritual and creative growth as a composer and a musician. The years of 1800-1802 were a transformative period in Beethoven’s life, and marked the beginning of his second stylistic period. As Beethoven’s outer hearing deteriorated, his inner hearing continued to grow.

Beethoven sought treatment in the village of Heilgenstadt in the late spring of 1802 until October of that year. Full of despair over the unsuccessful treatment, he considered ending his life. In a famous letter known as the Heilgenstadt Testament written to his brothers, he wrote “Thanks…to my art I did not end my life by suicide.”

Over and over in Beethoven’s music themes of victory over tragedy abound. In the internal struggle he faced, although his music showed the greatest despair and sorrow, it always transcended into triumphant victory. With that same inner struggle, Beethoven learned to transcend deafness and still be victorious in creating greater and greater masterpieces. During the late 1790s, Beethoven’s music began to show changes, as well as enlargement of form. After the Heilgenstadt Testament, Beethoven expressed dissatisfaction with his compositions and according to Czerny was “determined to take a new path.” [1] The changes included strong links between sonata movements, intensified drama, harmonic instability, motivic elements affecting the larger form, twelve measure structures, registral gaps, recitative and pedal effects.

Beethoven’s “Tempest” Sonata no. 17 Opus 31 No. 2, written in the somber key of d minor, is reminiscent of a violent storm with periods of calm and peacefulness. This Sonata is based on three different motives, which are then developed and used in different variations throughout the entire first movement, and continue throughout the entire sonata. The Sonata begins with a slow rolling arpeggio marked Largo on a dominant chord of A Major. This ascending arpeggio is the basic idea and the antecedent phrase of the exposition. This arpeggio is the dominant motive of this entire Sonata with an arpeggiated chord beginning the second movement and arpeggiated chords dominating the third movement as well.

Beethoven inner turmoil is clearly exposed in the tumultuous first movement, as well as the striving for inner peace in the impressionistic recitatives. The strong links between sonata movements is shown again as Beethoven uses the idea of the recitatives for the lugubrious second movement. Although the adagio illuminates the composer’s feelings of despair, at the same time shows transcendent spiritual growth with the beautiful lyricism in the second theme group of the Adagio.

Beethoven pushes the boundaries of harmonic instability by delaying resolution in the sonata to the very end of the finale. Beethoven has used the sonata form to support his creative demands instead of him conforming to the sonata form. It is as though the first movement is an introduction and transition for the upcoming finale which will take up in d minor where the first movement left off with the rolling arpeggios on the d minor tonic.

The finale gives way to a feeling of equilibrium with the principal motive of the arpeggio fading away on the d minor tonic. It is in the magnificent finale of the “Tempest” sonata where Beethoven shows victory over the funereal overtones of the Adagio which could be interpreted as a spiritual death and rebirth.

This sonata could be interpreted as Beethoven beginning to come to terms with his impending eventual deafness. The anguish and despair of the Adagio, the rage of the stormy moments of the first movement, contrasting with moments of calmness with inserted recitatives, the ferocious cadences and rhythms of the finale were his way of expressing how he felt about this affliction of deafness while writing the most extraordinary music and not being able to hear it.

Beethoven would live most of his life in a great deal of loneliness and despair with most of his life devoted to the development of his art and creativity. As this sonata was written towards the beginning of his second stylistic period many masterpieces would follow the “Tempest” sonata.

[1] Timothy Jones, BEETHOVEN The “Moonlight” and other Sonatas, Op 27 and Op 31, p. 15

![]()