Romantic Music

‘St Francois de Paule marchant sur le Flots’ Franz Liszt

‘Among the numerous miracles of St. Francis of Paola, the legend celebrates that which he performed in crossing the Straits of Messina. The boatmen refused to burden their barque with such an insignificant looking person, but he paying no attention to this, walked across the sea with a firm tread’…Franz Liszt

The story is beautifully captured in Liszt’s music. The calm strength of the opening hymn-like music is throughout the piece pitted against the roaring and crashing of the waves (represented by rushing scales and tremolos), finally emerging victorious in a glorious fortissimo restatement at the end of the piece.

Franz Liszt: Legend No.2 “St. Francois de Paule marchant sur le flots”

‘St. Frances of Paola Walking on the Water’

‘Among the numerous miracles of St. Francis of Paola, the legend celebrates that which he performed in crossing the Straits of Messina. The boatmen refused to burden their barque with such an insignificant looking person, but he paying no attention to this, walked across the sea with a firm tread’…Franz Liszt

The story is beautifully captured in Liszt’s music. The calm strength of the opening hymn-like music is throughout the piece pitted against the roaring and crashing of the waves (represented by rushing scales and tremolos), finally emerging victorious in a glorious fortissimo restatement at the end of the piece.

Many of Franz Liszt’s compositions sprang from religious inspirations. In 1863, he composed his 2 Légendes, a duo of programmatic pieces based on the legends of St. Frances of Assisi and St. Frances of Paolo. The work is among Liszt’s forward-looking composition and considered by some to be the roots of Impressionism.

The second piece of the set depicts the legend of St. Frances of Paolo who, not having any money to the fee, was denied passage on a ferry across the Straits of Messina. Mocked by the ferryman, he throws his cloak in the water and stands on it. Using his staff to guide his way across the Straits, St. Frances arrives ahead of the ferry and its passengers. Though this story served as Liszt’s inspiration of the piece, the end result is a magnificent universal depiction of struggle and triumph. The principal theme is announced immediately at the outset in unadorned octaves, and its emphasis upon the key of the mediant minor foreshadows the impending struggles. Stated again in the tonic key of E major above rippling tremolos in the bass, the theme is presented regally and in full glory. However, as the music progresses, the harmonic underpinnings become more violent and clash against the theme. Throughout the middle portion of the piece, the theme is nearly overwhelmed by the torrent of chords and surging chromatic lines. Following the harshest part of the struggle where unrelenting octaves build to their dramatic outcome, the theme returns in and triumphal splendor. Finally, a brief coda turns the mood solemn, like a prayer of thanksgiving. The principal melody then returns for a final statement in the bass and the piece concludes with heroic ascensions through the tonic triad.

Granados Inspiration for ‘The Goyescas’

Granados often called the poet of the piano is frequently compared with Chopin due to the highly ornamental figuration as well the influence of nationalist folk music in their melodies and rhythms. Granados indicated they are Goya-like or Goya-esque hence the name ‘The Goyescas’.

Regarding Goyescas, Granados wrote, “I am enamored with the psychology of Goya, with his palette, with him, with his muse the Duchess of Alba, with his quarrels with his models, his loves and flatteries. That whitish pink of the cheeks, contrasting with the blend of black velvet; those subterranean creatures, hands of mother-of-pearl and jasmine resting on jet trinkets, have possessed me.”

The story of Goyescas is based on a series of six paintings from Francisco Goya’s early career, inspired by the stereotypical young men and women of the majismo movement. “majos” and “majas” are known for their bohemian attitude and spirited nature. In this tale of the goyescas, the four main characters are Rosaria an enchanting aristocratic woman, her lover Fernando the captain of the royal guard, Pepa the maja and Paquiro the majo / toreador. A love triangle is formed when Paquiro flirts with Rosaria and invites her to a dance. Although she ignored his advances, Fernando did observe Paquiro’s advances and now does not trust Rosaria. Pepa also infuriated by Paquiro’s attentions to another woman seeks revenge. Later at the party, tensions are high and culminate in the two majos seeking to fight a dual. Later Rosaria sings a mournful ballad to a nightingale as she fears she will lose him. Fernando approaches and she begs him not to go to the dual and tries to reassure him of her devotion only to him. He still does not fully trust her, and wishes to prove his majismo, and promises to return to Rosaria victorious. Alas, Fernando is fatally wounded in the dual, and the grief stricken Rosaria drags him back to the bench where she sang to the nightingale and professed her love to him. Fernando then dies in her arms.

Quejas o La Maja y el Ruisenor the fourth piece of the Goyescas is the only one in the set with a key signature. The monothematic piece is based on a folksong Granados heard sung by a girl in the Valencia countryside. Granados transforms the haunting melody into five variations. It is the scene where Rosaria sings mournfully to the nightingale. The variations start in f# minor, move to b minor and back to f# minor which follows with the nightingale responding in a beautiful cadenza of elaborate figuration. Although there are five variations of the folksong, the piece is written in an improvisational manner where the variations flow directly into the next.

Quejas, o la Maja y el Ruiseñor

Alicia de Larrocha’s mesmerizing performance of Granados beloved

Quejas, o la Maja y el Ruiseñor (aka The Maiden and the Nightingale)

Chopin’s Musical Biography

Chopin Opus 35, A Musical Biography

Chopin’s Musical Biography & Mastery of Large-Scale Form

Chopin composed a Marché in 1837, stark and unadorned in melody but quite powerful. Opus 35 is built around this Marché and is the foundation of the sonata. Two years after the Marché was written as it was originally called, the sonata became published 1839. The outline of the sonata is:

I Grave/Doppio Movimento

II Scherzo

III Marche funèbre

IV Finale

Beethoven’s Sonata no. 12 op 26 is often thought of as an influence to Chopin’s opus 35. It has a similar construction; the first movement is a theme and variation. The second movement a scherzo, the third movement a funeral march and the fourth movement is a finale of unrelenting sixteenth notes. It is known Chopin played and admired it. Additionally he used it a great deal in his teaching. Many of his students reported working on it. Chopin’s earlier attempt at the sonata was in 1829 with his first sonata in c minor. Haslinger the publisher agreed to publish it in 1829 but later changed his mind. With Chopin’s works now being in demand, Haslinger had it engraved to begin publication. Chopin refused to authorize its publication but learned it was already in distribution in a letter from his father. He had recently made his home in Paris, following an unsuccessful stay in Vienna. Beethoven’s presence was still larger than life in Vienna as master of the sonata form, and Chopin wanted to prove he too had mastery of the large-scale form. He did not want to be judged by a composition written while he was still a student.

Chopin gave a preview performance of the Marché and reviews of this performance state Chopin had a ghostly appearance. The solemn feeling of the Marché brought tears to the eyes of the audience and Chopin removing the word funèbre from the title of the Marché intensified the music’s painful impact.

Marquis de Custine, left the most evocative corroboration in a letter of 22 October 1838 to Sophie Gay:

‘Consumption has seized that figure and has made of it a soul without a body. To say his farewells to us…then, to finish, funeral marches that, despite myself, made me dissolve in tears’.

Opus 35 is structured as a narrative, a story where each of the movements leads directly into the next. The stormy agitated chords of the coda in the first movement become the theme of the scherzo.

The four bar introduction to the first movement marked grave could just as easily be an introduction to the Marché. The finale which is a miniature sonata in and of itself sums it all up in one of the most mystifying enigmatic pieces ever written for the piano in a minute and a half.

The exposition in the first movement depicts a stormy life of a Polish émigré going first to Vienna then onwards to Paris, France. The turbulence and agitation of the first theme group in the exposition exhibits Chopin’s inner turmoil, which is strongly contrasted with a lyrical second theme group in the exposition. The sarcastic side of Chopin’s personality is shown in the Scherzo. The scherzo is fiery and displays a great deal of rage with explosive chords, which emulate the repeated tonic note as in the Marché. In Chopin’s life there was also a great deal of unrest over political problems in Poland as well as a tumultuous relationship with George Sand. Another source of controversy was his opposition to the romantic climate in which he was immersed in Paris. An ingenious composer with strong roots in classical and baroque music, Chopin’s music was also revolutionary. Lyrical trios in the second and third movements follow the classical sonata outline going to the relative major keys yet still have Chopin’s distinctive nocturne style. This put his signature on the classical sonata form. Chopin’s frail health continued to deteriorate and he was often consumed with thoughts of death, hence the foundation of the sonata is the Marché. Friends said he often stated “please make sure I am not buried alive”.

Chopin establishes mastery of large-scale composition (sonata form) with his own signature style in his only composition without dedication. Chopin’s contribution to the sonata form development is substantial in opus 35. As the sonata form developed from the Baroque period of pieces with multiple movements each with their own character this developed into the sonata form of the classical period, Beethoven first expanded the form than began to compress the form and link the movements together motivicaly. Opus 35 continues the development of the sonata form with creative mastery and development of motives, which penetrate each other and are linked together.

Funérailles – Harmonies Poétiques et Religieuses

I. Invocation

II. Ave Maria

III. Benediction de Deus dans la Solitude

IV. Pensee des Morts

V. Pater Noster

VI. Hymne de L’enfant a Son Reveil

VII. Funerailles

VIII. Miserere D’Apres Palestrina

VIIII Andante Lagrimoso

X. Cantique d’Amour

Many innovative concepts are explored in this suite such as constantly changing meters, no key signatures in addition to emphasis on the tritone. Liszt develops these innovations further in his later compositions. Fifty years later Liszt once again returned to the exploration of atonality in his Bagatelle ohne Tonart (Bagatelle Without Tonality).

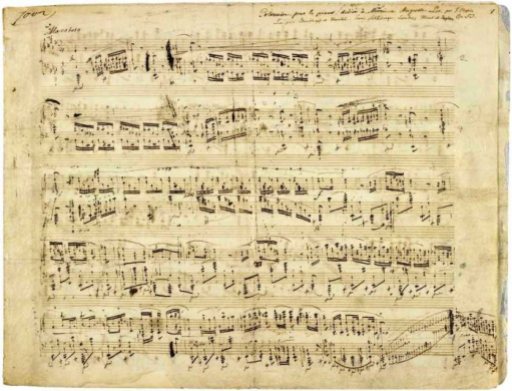

On the autograph manuscript of Funérailles,Liszt writes October 1849. Liszt indicated it was an elegy written as a tribute to three of his friends who died in the failed Hungarian Revolution. Prince Felix Lichnowsky, Count Laszlo Teleki and the Hungarian Prime Minister, Count Lajos Batthyany. It was a colossal defeat to the Hungarian people.

Death of Chopin October 1849

The intuitive use of material from Chopin’s heroic Ab Major Polonaise Opus 53 leads to speculation that this piece was more than an elegy to the Hungarian people but also an elegy to his dearly departed colleague F. Chopin.